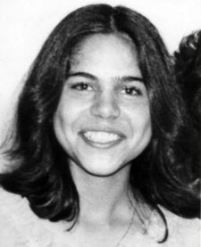

June 18th, 2023 will mark the 40th year since the death of Mona Mahmudnizhad. She was executed in Iran for being Baha’i and for teaching that faith to the children in her community. Her death, and especially her courage caught the attention of the world.

Mona lived her young life in service. Her father often said that Mona was the child he prayed for as he traveled many parts of the world teaching the Faith.

In 1980 Mona became even more focused when she turned 15, the age of spiritual maturity in the Bahá’í teachings. Mona had already begun following in her father’s footsteps as a Bahá’í teacher and wanted to teach young children, for whom she had a special love. A year earlier, she had applied to the Bahá’í Education Committee to be named to one of their sub-committees, but was refused because she was not 15 yet and not considered old enough for this service. When she received the news, she burst into tears.

In 1980 Mona became even more focused when she turned 15, the age of spiritual maturity in the Bahá’í teachings. Mona had already begun following in her father’s footsteps as a Bahá’í teacher and wanted to teach young children, for whom she had a special love. A year earlier, she had applied to the Bahá’í Education Committee to be named to one of their sub-committees, but was refused because she was not 15 yet and not considered old enough for this service. When she received the news, she burst into tears.

When she turned 15, she considered it her true first birthday and immediately registered as a Bahá’í youth and reapplied to the Education Committee. This time she was assigned to the Children’s Education Committee and began teaching Bahá’í children’s classes, which included the study of the great religions, developing spiritual qualities, encouraging the children to put their talents and education to the service of their fellow man and especially learning to appreciate the oneness and diversity of the human family.

Her service to the Faith accelerated greatly and actually began causing her problems. She spent so much time on Bahá’í activities that she was having difficulties completing her school assignments. At one point, the pressure was so great that she considered resigning from her Bahá’í activities, but could not do it. One day, when she was particularly tired, she asked her father to help her. He read her a passage from the Holy Writings that said, “The prophets of old wish they were alive in this day so that they may accomplish a service.” Mona immediately stopped talking about her problems and decided that she would carry out her duties to the best of her ability. She even began walking to school instead of riding a bus and saved enough pocket money to buy colored crayons, booklets and pencils, which she would give out as prizes to the students during Bahá’í children’s class. She also wrote prayers in the booklets and would give them to the children to memorize.

The persecution of the Bahá’ís extended to every level of society. While the Islamic authorities tended at first to single out only the more prominent members of the Faith for arrest and execution, cancellation of pensions, freezing of bank accounts and dismissal from employment, they extended their repressions even to the school level by expelling numerous Bahá’í children, especially those attending high school and university. They were only to be allowed to continue their studies if they denied being Bahá’ís. Bahá’í children, even when they were still allowed to stay in school, were forced to sit apart at the back of their classrooms, as “unclean infidels” and were not allowed to touch the other children. In one instance a Bahá’í child was forced to wash the brick floor of his classroom and sent home with bleeding hands, because he had refused to recant his Faith.

In Shiraz, a number of Bahá’í children had been expelled and Mona expected that her expulsion would come soon as well. But rather than fear it, she looked forward to it, since she would then be able to spend all her efforts for the Faith. When one of her friends was expelled, she said,

“Good for you. Now you can study the Bahá’í books one year longer. Pray that I will also be expelled.”

In the fall of 1981 (her second year of High School), she enrolled in a course on religious literature. Up to that point, like most Bahá’ís in Iran, her freedom to mention her Faith had always been strictly curtailed and was limited to brief and private responses to the questions of fellow students about the symbol on the stone in the ring she wore. However, when the literature teacher assigned the students a paper on the topic: “the fruit of Islam is freedom of conscience and liberty, whoever has a taste for it is benefitted,” Mona poured out her frustrations at being silenced in the poignant essay which follows.

While the paper Mona wrote is still in the hands of school authorities, the notes that she used to write the paper have been recovered:

‘Freedom’ is the most brilliant word among the radiant words existing in the world. Man has always been and will ever be asking for liberty. Why, then, has he been deprived of liberty? Why from the beginning of man’s life has there been no freedom? Always, there have been powerful and unjust individuals who for the sake of their own interests have resorted to all kinds of oppression and tyranny…

Why don’t you let me be free to express our goals in this community; to say who I am and what I want, and to reveal my religion to others? Why don’t you give me freedom of speech so that I may write for publication or talk on radio and television about my ideas? Yes, liberty is a Divine gift, and this gift is for us also, but you don’t let us have it. Why don’t you let me speak freely as a Bahá’í individual? Why don’t you want to know that a new religion has been revealed; that anew radiant star has risen? Why don’t you push aside that thick veil from your eyes?

Perhaps you don’t really think that I should have freedom. God has granted this freedom to man. You, his servant, cannot take it from me. God has given me freedom of speech. Therefore, I cry out and say, “His Holiness Bahá’u’lláh is the Truth!” God has given me freedom of speech. Therefore, in clear words, I write,

“Bahá’u’lláh is the One whom God has made manifest! He is the founder of the Bahá’í religion and His Book is the Mother of Books…”

The frank openness of her paper caused a furor at the school. The principal, who was considered a fanatical Muslim, called Mona to his office and warned her that she no longer had the right to mention the Bahá’í religion while on school grounds, a prohibition which Mona obeyed.

Ten months before she was killed, Mona had another extraordinary dream which was later related by family and friends. Following is the version transcribed from her diary.

She had been saying prayers with a small group of friends for several hours. After they left her home, she was so moved by the prayers that she went into the living room and sat down in front of a photograph of ‘Abdu’l-Baha6, meditated quietly and then fell asleep.

In her dream, she saw Abdu’l-Baha’s chair and desk, with a vase on it, as in the picture before her. She was very happy and said: “How happy I am to see your desk and chair.” At the same moment she saw Bahá’u’lláh entering the room. The Blessed Beauty went out into an adjoining chamber and brought out a box containing a beautiful red cape. He unwrapped it in front of her, saying, “This is the cape of martyrdom in my path. Do you accept it?”

Mona was speechless with happiness. Finally, she said, “Whatever pleases you…”

Bahá’u’lláh put the cape back in the box and returned to the adjoining room bringing back with him a second box, containing a black cape which he unwrapped and said:

“This black cape symbolizes sorrow in my path. Do you accept it?” Mona replied, “How beautiful are the tears shed in thy path.”

He put the cape back in the box and again returned to the other room, emerging with yet a third box containing an elaborately beaded blue cape of the same design as the others.

Without a word of hesitation, he placed the cape around her shoulders, and said: “This is the cape of service.” Then he seated himself in the chair and said to Mona: “Come and take a picture with me!”

Mona was breathless with astonishment at the bounties being showered on her and could hardly walk. She looked up and saw a man sitting behind an old-fashioned camera covered by a cloth. Bahá’u’lláh repeated his instruction but Mona could not move.

Then Bahá’u’lláh took her arm, saying, “Mehdi, take our picture.” And he took a picture of them together. The flash of the camera wakened her abruptly and she pleaded tearfully to be able to finish her dream and then fell asleep again. Bahá’u’lláh had left the room. Only the photographer remained, carrying the tripod and camera on his shoulder as if to leave. He turned around and asked Mona to convey his love to his children. But Mona could not tell which “Mehdi” he was since there were many people by that name in the long history of the Faith and in her own community. But still he looked familiar to her. “Mehdi” was busily tying his shoes and noticed that Mona did not recognize him. As he was leaving the room he turned and said, “I am Medhi Anvari.” Mona instantly recognized him as one of the Bahá’ís of Shiraz who had previously been killed.

Beginning at the age of 13, Mona had begun to dream and write about her father’s death in a startling way. Some of these writings are now preserved among her papers.

The months following Mona’s dream of the capes were tense for the Bahá’í community. Arrests and executions of Bahá’ís were taking place all over the country. In Shiraz, the Public Prosecutor had initiated mass arrests in late October 1982. While it was almost a foregone conclusion that Mona’s father would be arrested because of his service on the Local Spiritual Assembly and the Auxiliary Board, few suspected that Mona would also be singled out.

The arrest occurred at 7:30 pm on October 23, 1982. Mona was at home with her parents. Her sister, Taraneh, was now married and no longer living with her family. When the doorbell rang, Mona was studying for a test she had in ~ English, her father was writing some letters in a notebook and her mother was doing housework. Her father opened the door and four armed revolutionary guards demanded entry. The Guards said that they were appointed by the Public Prosecutor of Shiraz to inspect the Mahmudnizhad household.

Before the search began, Mona asked to put on her chador (Islamic head covering) and was escorted to her room so that she could retrieve it. Her father asked if her mother could put on a jacket. Then the three members of the family were ordered to sit in their living room, with Mona and her mother flanking their father. One Guard held a gun on the Mahmudnizhads, while the others meticulously searched and ransacked their rooms.

At one point, Mona’s mother whispered to her father, “What shall I do. They are going to arrest you.” Her father replied, “Say the prayer “Remover of Difficulties” to yourself and turn to Abdu’l-Baha.” He then fixed his eyes on the picture of Abdu’l-Baha in front of them. Mona was the picture of calm and continued to study her English lesson. At one point, she even asked her father a question, but the Guard ordered her to be quiet.

When the search ended, Mona’s mother became terribly upset when the Guards ordered both Mona and her father to come with them. She said, “I can understand that you would want to take my husband with you, but why do you want to take Mona. She is only a child.” According to one account, one of the Guards replied, “Do not call her a child. You should call her a little Bahá’í teacher. Look at this poem. It is not the work of a child. It could set the world on fire. Someday she will be a great Bahá’í teacher.”

When the search ended, Mona’s mother became terribly upset when the Guards ordered both Mona and her father to come with them. She said, “I can understand that you would want to take my husband with you, but why do you want to take Mona. She is only a child.” According to one account, one of the Guards replied, “Do not call her a child. You should call her a little Bahá’í teacher. Look at this poem. It is not the work of a child. It could set the world on fire. Someday she will be a great Bahá’í teacher.”

The guards continued to heap abuse on both Mona and her father, causing her mother great anguish. At one point her father told her not to be worried, that he considered the guards to be his children and Mona their sister, that the guards had been assigned by God to come to their house and take them away together. Mona reassured her mother, saying, “Why do you beg these people? What offense have I committed. Have I been a bad girl? Do we have smuggled goods in the house? They arrest me just because I believe in Bahá’u’lláh. Mother, this is not going to prison, it is going to Heaven. This is not falling into a pit, it is rising to the moon.”

When the Guards took Mona and her father, they also confiscated all of their papers and some cassette tapes of Mona’s chanting.

While they did not know it at the time, Mona and her father were among the first of 40 Bahá’ís in Shiraz, including six women, who were arrested that night or during the next few days. After the arrest, both were blindfolded, taken to Seppah prison and then led to separate quarters. Mona was given a piece of paper to hold and led down a long corridor and then into a large room where the blindfold was removed. Since it was around midnight, the room was dark.

More than 40 women were in the room at the same time, Mona later recounted. As her eyes adjusted to the light, she could see windows in the room covered with metal bars. The room was also dank and had poor ventilation. Since Mona was the first Bahá’í woman to reach the prison, she was all alone and knew no one in the room. She was met by the woman-in-charge, who asked her crime. Mona replied that her crime was being a Bahá’í. The woman then issued her two blankets and showed her to a space where she could sleep. The room was so crowded, however, that everyone had to sleep on their sides.

In mid-January, shortly after Mona’s third interrogation, Mona’s mother was contacted and told that Mona was considered not guilty and would be released on bail, provided that the Mahmudnizhad’s could raise bail money.

Mona’s bail was set initially at about $35,000. Mrs. Mahmudnizhad tried to get the Court to accept a mortgage on the small apartment that the family owned in Shiraz, but that was not accepted because the family did not have a clear title. Mona was not released. The presiding judge then raised Mona’s bail to about $88,000.

But after Mrs. Mahmudnizhad had turned the title over to the authorities, Mona was still not released. The authorities took the property anyway and then arrested Mrs. Mahmudnizhad when she came to the prison with the documents for Mona’s presumed release.

While the Islamic authorities did release six Bahá’í prisoners, Mona and 14 others remained in jail. Her mother remained in jail with them until a week before Mona was executed.

About 10 days after Mona’s mother was imprisoned, the Bahá’í prisoners were startled to hear an announcement calling all “Bahá’í sisters” to an area on the roof of the prison. It was the first time that the word “Bahá’í” had ever spoken over the intercom. When the women reached the area, all the Bahá’í men who were being held in the prison were there too. The Mahmudnizhad family, father, mother and daughter, were together in prison for the first and last time.

On June 13th, Mona’s mother was suddenly released. Before she left the prison, all of the women hugged her. Mrs. ‘Izzat Ishraqi, whose daughter, Rosita, was soon to be married, asked Mrs. Mahmudnizhad to attend the wedding on her behalf, and asked her to take a red carnation for each of the women prisoners. Then Mona took her in her arms and they kissed for the last time.

“Mother,” said Mona, “Just as you were encouraging and assuring to everyone while you were here from now on you should be the same and encourage the friends (outside) to be patient and tolerant.” They kissed again and her mother left the prison and went to stay with Taraneh. While there, she told Taraneh about each of the women and visited the mothers who had daughters in prison.

On Thursday, June 16, six Bahá’í men were executed –Abdu’l Hossein Azadi, Bahram Afnan, Jamshid Siyavushi, Koorosh Haghbin, Bahram Yalda’i and Enayat’u’llah Ishraqi. Three of the men were related to the women prisoners. Jamshid Siyavushi was the husband of Tahirih Siyavushi. Enayat’u’llah Ishraqi was the husband of ‘Izzat Ishraqi and father of Roya Ishraqi. Bahram Yalda’i was the son of Nusrat Yalda’i.

The next day, the Bahá’í community was filled with activity, with Bahá’ís from all over the city visiting the families of the martyrs. They brought flowers and, while their eyes were filled with tears, they were smiling and wearing colourful clothing, rather than the traditional mourning garb.

On Saturday, Mona’s mother and sister visited the prison, along with the families of the othr women prisoners, who did not yet know about the killings of the 6 men. Only four Bahá’ís at a time were allowed in to visit the prisoners, who were kept behind a glass partition and had to talk through telephone handsets. Mona’s family brought her some watermelon, along with a scarf and a new towel.

Taraneh was chosen to tell Mona about the martyrdoms. When she greeted her, she told her that six Bahá’í men had been executed14. Mona’s eyes filled with tears. She put her hand over her heart and asked who they were. As Taraneh named each one, tears welled up in Mona’s eyes and she pressed her hand closer to her heart. In a whispered tone, she said, “Good for him! Good for him!” after each name.

When Taraneh finally spoke the name of Mr. Ishraqi, Mona began to weep openly, saying, “Good for them all!” Then she said in a loud voice, “Taraneh, I swear to the Blessed Beauty and to God that these tears are not tears of sorrow. These are tears of happiness. Don’t you ever think that I’m crying out of sorrow. It is only out of happiness.”

The hangings of the 10 women took place on the eve of June 18, 1983, under cover of darkness, in a nearby polo field. The driver of the bus, who later met the grandmother of one of the young women, told her, “They were all in the most excellent spirits and were singing many songs on the way. I could not believe that they knew they were going to be executed. I have never seen people in such high spirits.”